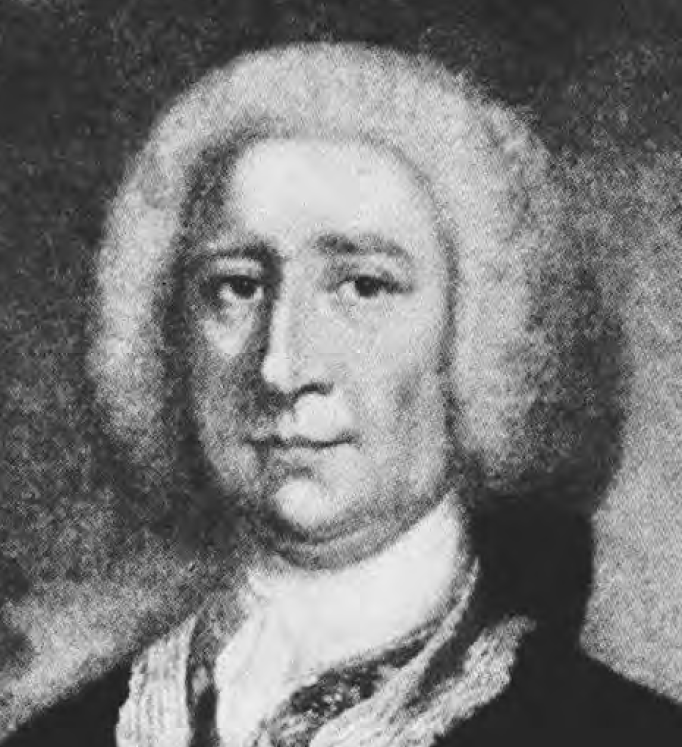

William Shirley was an English governor of Massachusetts (1741–1756) and of the Bahamas (1761–1769). A consummate politician with expansionist views for the British Empire in North America, William Shirley directed much of the early effort in the French and Indian War (1754–1763). William Shirley was born in Preston, Sussex, England, on December 2, 1694; Shirley attended Cambridge University before immigrating to Boston in 1731.A

In Boston, Shirley carefully employed family connections in England to protect the governorship of Massachusetts for himself in 1741. When King George’s War (1744–1748) began, Shirley cajoled the Massachusetts legislature into financing an expedition against the French stronghold at Louisbourg, on Cape Breton Island.

After the fortress fell to the British in 1745, he rightly claimed much of the credit for so vigorously backing the effort. In recognition of this success, the ministry in London awarded Shirley a colonelcy and ordered him to raise a regiment of colonials. He moved quickly to improve Massachusetts’ defenses and consulted with British leaders on proposed plans to invade Canada. In 1746, 1747, and 1748, the ministry repeatedly abandoned such plans.

This stymied Shirley’s dream of projecting British power into Canada. With the end of the war in 1748, Shirley found himself at the center of a political realignment in Massachusetts. When a group of his former allies organized a campaign to have him removed from office, Shirley sailed for England in late 1748 to defend his conduct. He did so quite ably. While in London, he received the prestigious appointment as one of the commissioners to negotiate with the French the final settlement of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748), ending King George’s War (known as the War of the Austrian Succession in Europe).

William Shirley pushed his expansionist views of British power on both his fellow commissioners and ministry officials in London. The ministry held a more limited conception of the empire, however, and Shirley was recalled in 1752. Shirley returned to Boston in 1753 to a warm reception.

Conscious that the possibility of another war with France was never far off, he immediately set about strengthening the colony’s defenses. In 1754, he organized an expedition to Maine to secure Massachusetts’ hold over that territory in response to reports of French encroachment. Later in the year, he vigorously supported the plan of colonial union discussed at the 1754 Albany Conference.

William Shirley spent the winter of 1754–1755 organizing an ambitious campaign to secure Nova Scotia. Although the ministry had not sanctioned such a plan, officials were impressed with Shirley’s initiative and quickly incorporated this northern component into their broader military plans. The home government also authorized Shirley to begin recruiting for his defunct regiment, which he did with great enthusiasm. In Massachusetts alone, Shirley raised a force of 7,000 men, which far exceeded his superiors’ expectations.

The arrival of the new British commander-in-chief in North America, Major General Edward Braddock, produced a conference of governors in Virginia in April 1755. Shirley so impressed Braddock with his confidence and knowledge that Braddock appointed him second-in-command of British forces in North America. Despite Shirley’s lack of experience leading troops in battle, Braddock also authorized him to lead an expedition against Fort Niagara.

Shortly before launching the attack in the eastern Great Lakes region, Shirley received news of Braddock’s defeat and death in the Battle of the Monongahela (during which his son had been killed). Now commander of all British forces on the continent, Shirley hesitated about the wisdom of proceeding as planned. Instead, he sent his forces to Fort Oswego, deciding that the campaign against Fort Niagara would wait until the spring. In December 1755, at a conference of governors held in New York, Shirley outlined a bold plan of attack for the 1756 spring campaign.

He vowed to push on with the efforts that had stalled the previous year. Shirley’s enemies worked vigorously against him, however. They penned letters to officials in London decrying Shirley’s inability to hold such a high command. Shirley was unaware of the smear campaign, but he had assumed the ministry would replace him with an experienced military leader.

In the meantime, he devoted his energy to building up the British forces. As spring 1756 approached, Shirley scaled back his campaign plans, announcing that the expedition against Crown Point would take precedence over other ventures. By mid-1756, William Shirley’s vacillations had angered a sufficient number of colonials to bring about his recall. His successor, John Campbell, Lord Loudoun, arrived in New York City in mid-July 1756, amid rumors that Shirley had been relieved of command in disgrace.

Shirley immediately sailed for England to answer charges that his accounts while commander in chief had contained irregularities. He was not cleared of wrongdoing until 1758. From 1761 to 1769, William Shirley served as governor of the Bahamas. He retired in 1770 and died in Roxbury, Massachusetts, on March 24, 1771.

Related Reading: Rum Trade Trade Between Caribbean Colonies, North America and Great Britain