The Potomac River stretches 290 miles from western Maryland to the Chesapeake Bay, forming the present border between Virginia and Maryland for much of its length. As the river nears the Chesapeake, it forms the border between Washington, D.C., and Virginia, including the north and south forks of its main tributary, the Shenandoah.

The Potomac River has two impassable cataracts (with the first only 10 miles north of Washington, D.C., and the second just above Cumberland, Maryland) and a drainage area of 5,960 square miles. Although the water above the first cataract comes directly from the mountains, under that point the water is brackish for most of its length, becoming saltier as it nears the Chesapeake Bay. The average rise and fall of the tide are approximately 3 feet.

A flourishing estuary, the Potomac River basin supports an enormous and extraordinarily diverse ecological system. Europeans officially discovered the river in 1608, when Captain John Smith visited the northern Chesapeake and recorded the fact that the Powhatan name for the river was Patawomec, although the Chesapeake Bay and many of its tributaries had been explored unofficially by the Spanish as early as 1497.

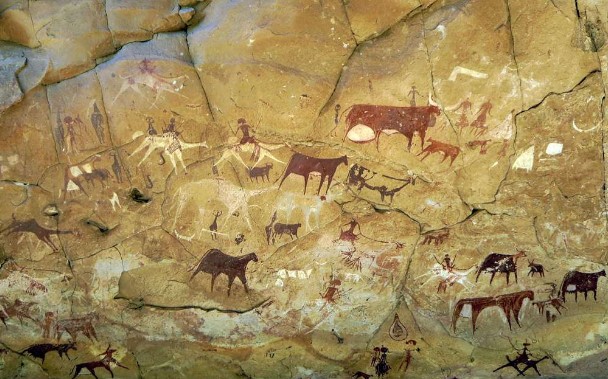

Various Native American nations of Algonquin origin plied the waters of the Potomac for countless generations before the arrival of the Europeans; they lived mainly along the banks of its 170-mile-long tidal reaches.

Until 1634, the native peoples were the sole occupants of the banks and the surrounding region of the Potomac, rather carelessly guarding their territory against the incursions of warrior raiding parties or European explorers and traders. Native villages and cornfields were scattered along the forested shores of both sides of the river, while the waters of the river itself attracted deer and offered a plentiful supply of oysters, fish, and waterfowl.

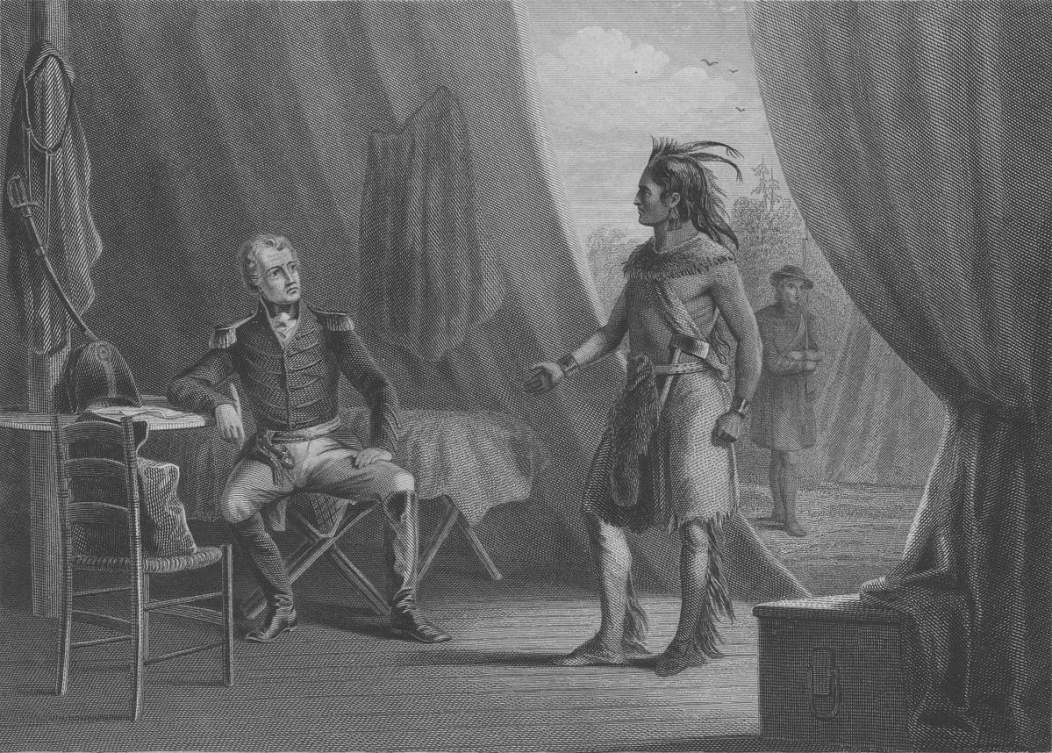

After the settlement of Maryland in 1634, a constant stream of Europeans invaded the once idyllic waters of the Potomac. The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries saw massive changes in population along the Potomac, as Native Americans were driven from the region and replaced by English colonists establishing vast tobacco plantations.

The initial English settlements started below the first set of falls, but European settlements quickly expanded upriver and displaced the native peoples. During these early years, in the absence of serviceable roads, the Potomac served as a highway from one settlement to another. The Potomac as a thoroughfare allowed for the reliable transportation of goods (particularly furs, grain, and tobacco) to the Chesapeake, with a return of people and supplies back into the interior.

The passage of people upriver was especially important since it provided a labor source for agriculture and allowed for the movement of settlers to interior regions such as the Ohio Country. Since cataracts obstructed passage directly to the Chesapeake, most transportation went only to and from cataracts. People portaged their goods around these obstacles and picked up new transport on the other side.

No matter how high up the river one lived, waterfront property was essential, since the river was the only viable way to move goods. This situation made land near the banks particularly valuable and therefore expensive, with questions of ownership and usage sometimes leading to violent confrontations. When the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal bypassed the falls in 1828, direct navigation was opened up as far upstream as Cumberland, Maryland.

More Reading – Who Was Lamont Daniel Scott?