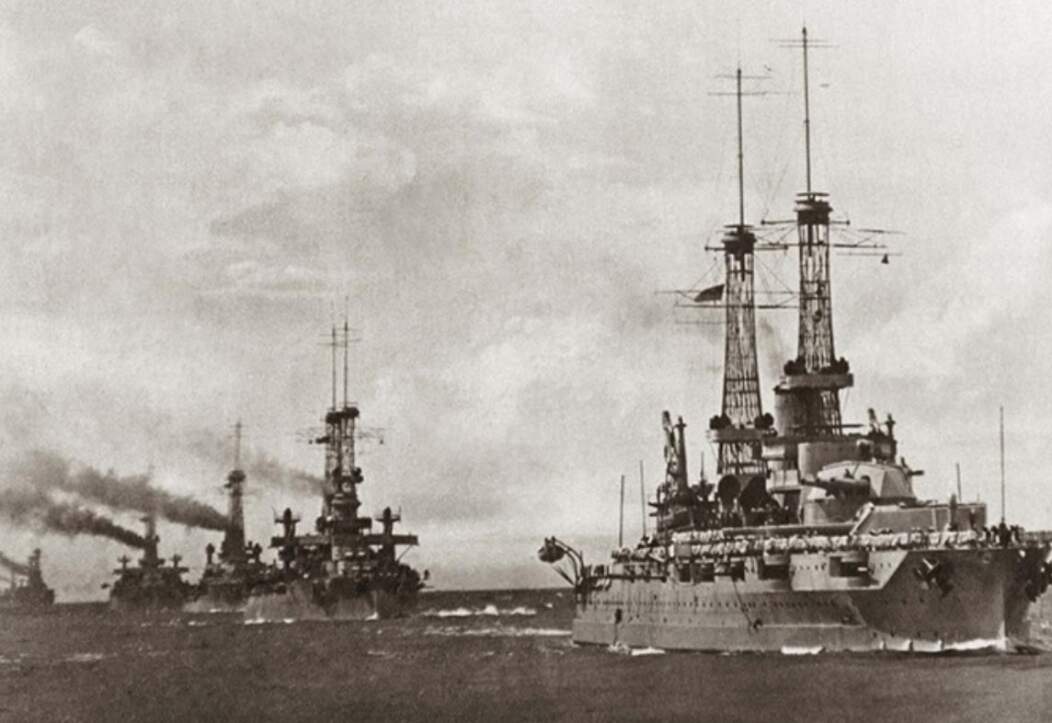

Naval War in 1917, when at sea, the British Grand Fleet was now commanded by Sir David Beatty in place of Sir John Jellicoe, who had succeeded Sir Henry Jackson as First Sea Lord in the previous November, the year 1917 passed without a single outstanding engagement. Since Jutland, the German High Seas Fleet had run no risk above the water of again seriously challenging Britain’s sovereignty of the sea, though her submarine campaign was pursued with over-increasing vindictiveness. Risking rupture with the United States and other neutrals whose shipping and subjects were thus exposed to wanton attack, she inaugurated ‘unrestricted’ U-boat war on February 1. “Give us two months of this,’ said the German Foreign Secretary to the American Ambassador in Berlin, “and we shall end the war and make peace.”

The argument was that the Allies’ losses in tonnage, already more than they could bear, would increase to such an extent that they would be starved into submission. The United States, with President Wilson as spokesman, replied by severing diplomatic relations with Germany, but it was not until April 5 that she formally declared war against her. Cuba followed suit on April 5, Panama three days later; and Brazil on June 2. Germany could afford the risk of offending the smaller American republics, but her defiance of the United States was a fatal blunder.

She relied on her submarines to prevent the transport of American troops across the Atlantic, at least until they were too late to affect the issue. The first American contingents crossed unharmed and arrived in France on June 26. It was not until the following year, however, that the new American army was ready to throw its weight onto the scales on the Western front. The naval resources of the United States were at once placed at the Allies’ disposal, the American destroyer squadron in particular being of great service in helping in the protection of trade-off the Irish coast, Proof of the closeness of cooperation between the British and United States navies was afforded in June 1917, when Vice-Admiral Sims, commanding the United States Naval Forces in European Waters, was given the command of the Irish station during the absence of Vice-Admiral Bayley on sick leave. No foreign naval officer had ever previously held the command of British ships, as well as his own, off the British coast.

Apart from the relentless submarine campaign, which every week exacted a heavy toll yet never brought the Allies within measurable distance of the starvation point to which the Germans had been so sure of reducing them, the enemy’s operations at sea were restricted to the destroyer and torpedo-boat raids in the Channel from Zeebrugge.

Some of these did a certain amount of damage to patrol boats and bombarded Ramsgate, Broadstairs, and Margate (February 27 and April 26) with little effect, saving the lives of women and children. One memorable incident in these minor operations in 1917 was the raid on Dover on the night of 20–31 April, when 6 German destroyers, after firing several rounds inland, were caught on their way back by the British destroyers Broke (Commander R. G. E. Evans) and Swift (Commander A. M. Peck), the advance ships of the British destroyer guard in the Straits of Dover.

The Swift, which was leading, dashed between two of the retreating destroyers and, turning, sent one of them to the bottom with a torpedo. The Broke rammed the third vessel, and while the two ships were locked, an old-fashioned hand-to-hand fight took place on the Broke’s forecastle, in which the German crow was beaten back. Two minutes later, the Broke wrenched herself free, and the German destroyer sank. Ten German officers and 108 men were rescued at the close of this dashing affair.

Read More: Rare Picture of King Tutankhamun’s Mummy