YUROK, their southern neighbors, called them Tolowa. The Tolowa tribe lived nearby Lake Earl, so, their name translates as lake dwellers. Hennaggi and Tataten were the other two native bands. TAHL-oh-wah was one of them. Due to their villages along the Smith River and its tributaries, all three groups were called Smith River Indians by non-Indian settlers.

The Crescent Bay of the Pacific Ocean was home to other villages. Tolowa territory extended slightly across the border into southwestern Oregon from present-day California (in the northwest corner of the territory). In terms of culture, they are classified as CALIFORNIA INDIANS, which is a part of the California Culture Area.

The Tolowa tribe were among those ATHAPASCANS who broke away from kin in present-day northwestern Canada and migrated southward like the HUPA who lived south of Yurok lands and the TAKELMA and UMPQUA who lived north in Oregon. There are 10 distinct languages spoken by the Tolowa tribe, including Athapascan languages spoken by local groups in SW Oregon such as Upper Umpqua, Coquille, Tututni, Chetco, Tolowa, Galice, and Applegate River people), the Trinidad Rancheria (Chetco, Hupa, Karuk, Tolowa, Wiyot, and Yurok),

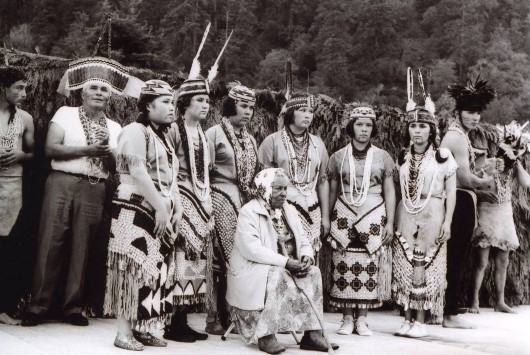

A Tolowa village is politically autonomous, with kinship ties defining ties among villages. They call themselves Hush or Huss in their Athapascan dialect. The headman and shaman of each village were different. Some tribes allowed women to become shamans, but others did not.

Possessions such as obsidian tools, dentalium shell beads, red-headed woodpecker scalps, basketwork, and sea lion and seal skins played a significant role in political influence. Different tribes traded such items regularly; dentalia strings were particularly used as a medium of exchange. It is not unusual for intertribal marriages to take place, the wives living in the villages of their husbands. A dugout canoe made from redwood logs was the primary mode of transportation used by the Tolowas for fishing and hunting sea mammals offshore.

Most of the year, they stayed in their coastal villages, numbering as many as eight, and moved upriver to fish for salmon, gather acorns, and hunt in the forests in summer and autumn. Permanent semi-subterranean houses were built with redwood planks; they were nearly square and had round entrances, gabled roofs, and central smoke holes.

In the interior of the building, the floor was sunken, except for ground-level ledges that were used for storage. A fire pit was located at the center of each structure for heating and cooking. The sweathouses also served as a clubhouse for single men and adolescent boys. During the late 18th century, explorers are believed to have brought disease to the Tolowa that forced them to abandon a village.

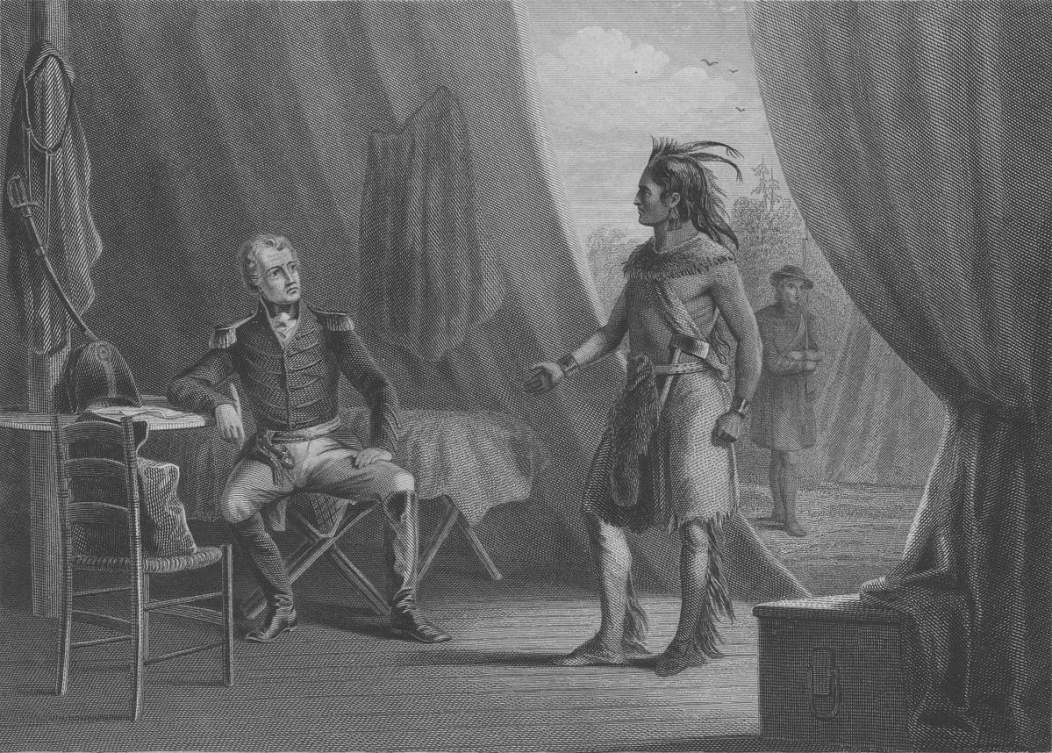

It wasn’t until 1828 that a Jedediah Smith expedition traversed their homeland that they made their first contact with non-Indians. As a result of the California gold rush, increased traffic was seen on their lands starting in 1849. A non-Indian settlement first emerged in 1852, which became Crescent City. Newcomers and Tolowa engaged in violent conflict. The Klamath Reservation in southern California, south of Tolowa territory, forced many Tolowa to live on a military reservation in 1852–55.

The majority of them were moved to Oregon reservations in 1860. The Tolowa were granted a separate reservation on the Smith River in 1862, but it was terminated six years later. There were a number of religious revitalization movements among PAIUTE tribe members in 1872, including the Ghost Dance of 1870, founded by Wodziwob, a prophet. Congress established the Smith River and Elk Valley Rancherias in 1906–08 after establishing small reservations for a number of landless tribes.

During the 1880s, John Slocum of the SQUAXON founded the Indian Shaker Religion (Tschadam), which was practiced by some Tolowa in 1927. In 1958, the Rancheria Termination Act terminated the two rancherias and cut off federal funding. In 1983, tribes regained ownership of protected lands. With the help of the Lucky 7 and Elk Valley casinos, Tolowa has undergone a cultural resurgence.